How Marou put Vietnam on the world’s chocolate map

Photo courtesy of Marou Chocolate

Asian expansion plans include cafes from Japan to Singapore

HO CHI MINH CITY — In the world of chocolate, something has changed in the last decade, as subtle as the cherry aftertaste of a fine truffle. In London cafes and Tokyo grocers, connoisseurs were persuaded to buy new bars from Vietnam, a communist country better known for coffee and rice exports.

And few have done as much to showcase the country’s cacao bona fides as Marou. The chocolate maker has taken a journey befitting a Silicon Valley upstart, replete with quests by motorbike, home kitchen hacking, and international awards. Marou was founded in 2011 by a pair of French friends, who went from plucking pods out of the Vietnamese countryside for experimentation, to shipping chocolate bars wrapped in luminous colors to 32 countries. Now, with one decade under its belt, Marou is looking to the next one. It aims to multiply its network of smallholder farms fivefold. From Shanghai to Singapore, it plans to go overseas with Maison Marou, a chocolatier where customers hold business meetings over mocha, or watch an industrial-grade roaster swivel trinitario beans. And the company, which last week got a new round of investment from Mekong Capital, will use the undisclosed sum to try to win over a new demographic: local consumers.

“Vietnamese like chocolate, but they really see it as a flavoring, like on a cake or a Choco Pie,” co-founder Vincent Mourou said in an interview at a Maison Marou cafe.

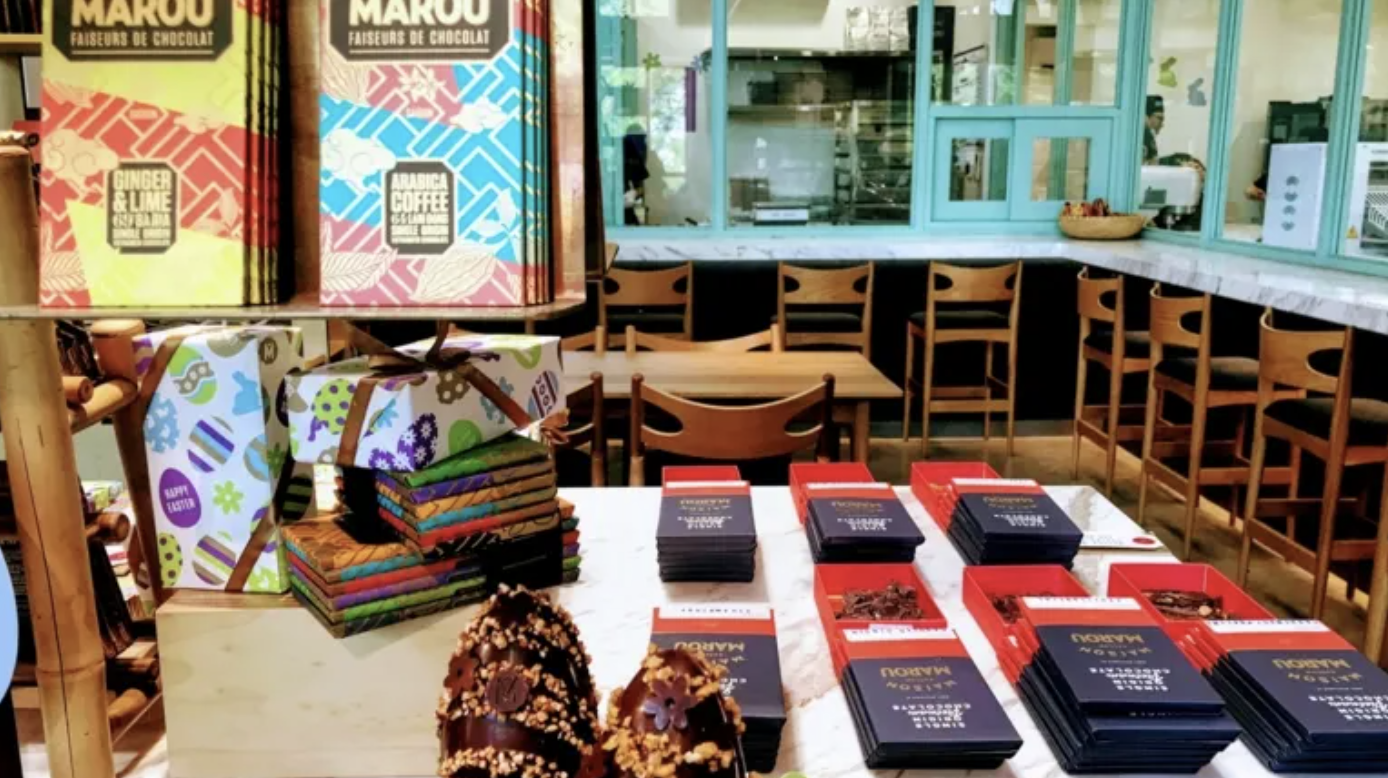

A Maison Marou employee works in front of an industrial roaster set up so the chocolate shop’s customers in Ho Chi Minh City can watch. (Photo by Lien Hoang)

He and his Japanese-French co-founder, the late Sam Maruta, did something that hadn’t really been done before, extracting a bean that wasn’t much of a priority in Vietnam, and convincing foreigners to pay gourmet prices for the artisanal product. But for locals, the obstacles are price and palate. In a country where set meals often end with a plate of guava or pomelo, 78% dark can be a bitter change. And for, say, a nurse eating $2 pho at lunch, a $5 chocolate bar is a bigger ask.

Marou will market so co la to Vietnamese with sweeter concoctions, tasting classes, pop-up patisseries, and farm tours. That includes a new lineup for the autumn: smaller bars, with nuts or fruit. Later, the company will distribute a wider array of chocolate-adjacent confections, though its cafes already sell macaroons, brownie mix, and dozens of other items beyond candy and drinks. These cafes will make their debut abroad after the pandemic, Mourou said, naming Japan and Hong Kong as early markets.

Sam Maruta, left, and Vincent Mourou founded Marou Chocolate in Vietnam. (Courtesy of Marou)

“I have people knocking on our door to partner,” Mourou said, seated at a window nook while trees billowed and motorbikes flitted behind him.

He gestured around the Maison Marou, a burst of colors from the sunglow footballs of cacao (for display) to the branded straws and board games (for sale). In between bites of eclair, diners watched the roaster whir and the employees carve into slabs of single-origin chocolate. As Mourou put it, “Each shop is actually a minifactory of its own.” Vietnam is by no means a chocolate powerhouse. Belgian and Swiss chocolatiers are not under threat, and West Africa still dominates sourcing. Ghana exported $1.8 billion of cocoa in 2019, versus Vietnam’s $5.3 million, according to UN Comtrade. Still that is double what it exported in 2009, and because its industry is less entrenched, Vietnam may have an opening.

The U.S. Supreme Court is hearing a lawsuit against chocolate corporations accused of using child labor in Ivory Coast. Mourou blames such labor problems partly on an unhealthy drive for cheap cacao, while a Vietnamese official says Vietnam can step in with more responsibly sourced beans. That extends to the environment. Last week an academic study calculated deforestation caused by consumption in rich nations, finding an average of four trees felled a year per consumer. It linked German chocolate imports, for example, to the lost forests in Ghana and Ivory Coast.

Marou popularized single-origin dark chocolate from Vietnam. (Photo by Lien Hoang)

Marou is helping develop an agroforestry project, planting cacao among other trees rather than clearing them, in Madagui, 100 km northeast of Ho Chi Minh City. The project will admit tourists when it opens. The company is also seeking farmers for direct partnerships, aiming to cover 1,000 hectares within 10 years, about five times the current figure. It gives landowners fermented seeds and training, such as in composting and trimming. Mourou hopes it will be the start of a greener, more productive phase in the global industry.

“Vietnam would be very early to apply that,” he said. “Vietnamese farmers are educated, they’re switched on.”

He’s an emotive interlocutor, stretching his arms wide when he describes the company’s first big purchase, a wet grinder, and reminisces about the early months with Maruta. Ten years ago in February, the two friends stood around the black walls and marble counters of Maruta’s kitchen on the Saigon River. They crushed cacao seeds, toted home from Ba Ria by motorbike, into a powder that tasted granular, strong and fruity. In the coming months there’d be more trials and more seeds — whisked into 50 iterations of chocolate and stored in a wine fridge — until they created a treat that would kick off a new business.

Since then, Marou has nabbed several accolades, including an Academy of Chocolate Award, and across the Southeast Asian country more broadly, roughly 20 other chocolate artisans have sprouted up, from Belvie to Vietnam Chocolate House. Chocolate is “something that really brings pleasure to people, makes people happy,” Mourou said. “It’s one of the few things most people can agree on.”

Like what you read?

Discover Vietnam’s coming-of-age food and drink scene with one of our tours and experiences exclusively available at Saigon Social